I was in Sacramento on Wednesday to have a meeting about the historical clothing books I'm creating for California State Parks. We're getting close to publishing volume 1, "The Mexican Era, 1822-1847." It will be a history of all of the clothing worn in California except traditional Native American. There will be 13 chapters divided into three sections: A. Paisanos (Californios, Franciscans, Native Californians, and Soldados); B. Newcomers (Colony Ross, Mountain Men, Hudson's Bay Company, Merchant Seamen, and Euro-American); and C. California Conquest (US Navy, Marines, Army, and Volunteers). Each chapter will have an overview of the clothing or uniforms, with detailed color plates by me, eyewitness images and descriptions, additional drawings by me, and a bibliography. In addition, there will be three appendices: Clothing California (how California acquired its clothing, fabrics, news about fashion, etc.); Goods for Sale (a list of things you might have been able to purchase in California during this era); Horse gear (Californio and American made "Spanish" saddles, Euro-American (English and "Hybrid" saddles), and Native American (used by HBC and trappers). And, finally, there will be an extensive glossary of terms used in the book with definitions of fabrics, trims, horse gear, garment types, etc.

Volume 1 will come out in the first half of 2019.

Volume 2, which should also be out next year, will cover the early American period, 1848-1860, which will be mostly Euro-American clothing worn by immigrants, miners, gamblers, dance hall girls, craftsmen, etc. There will also be chapters on entertainers, Californios, Native Californians, and the so-called "foreign" miners including the Chinese, Chilean, Malays, Hawaiians, etc.

Volume 3, also out next year, is about living history in California State Parks - how it developed, what it is today, how to organize and maintain living history programs, etc.

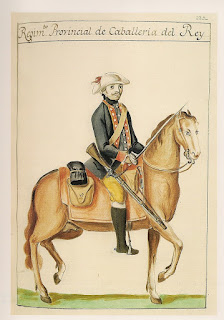

The illustrations I am creating are still in the development stage. I'm including two of my sketches with mocked-up captions, and just a peek at one of the finished color plates - Californio vaqueros of the 1820s - 1830s.