A.

A.

Several months ago I was asked by the museum at Mission San Juan Capistrano in California to help them find and direct craftspeople to make replicas of the kinds of arms used by the Spanish presidial cavalry in the late 1700s - the kinds of men who would have formed the cuartel, or guard, at the Missions. These replicas will be a part of a new exhibit at the museum. https://www.missionsjc.com

B.

B.

I've enjoyed working on this project, which is directed by Megan Dukett, the Education and Interpretive Program Director at San Juan Capistrano, and seeing the amazing creations of the artisans. The first replica to be completed is this copy of a Model 1728 Spanish Cavalry broadsword - the kind of weapon used by Spanish frontier soldiers across the West, from Texas to California. Its creator is John Logan, a skilled craftsman and owner of Iron John Logan, specializing in fine blacksmithing, woodworking, and leather. I provided the research information, but John provided the artistry. http://ironjohnlogan.com, https://www.facebook.com/ironjohn.logan

C.

C.

D

D.

There has long been confusion about the meaning of the Spanish term espada ancha, though I cannot understand why. Many years ago it became attached to Mexican short swords that were usually carried on the saddle. Espada, of course, means "sword," and ancha means "wide" or "broad." So, a literal translation is quite simply, "broadsword," not "shortsword." In fact, from period literature we know that these short swords were called machetes - and still are by Mexican horsemen.

E.

E.

The late, and great, historian Sidney Brinckerhoff, seems to have had a part in this confusion of terms by misnaming these short machetes espadas anchas in his classic study, with Pierce A. Chamberlain, Spanish Military Weapons in Colonial America 1700-1821 (Stackpole Books, 1972). Some years ago, in an exchange of email messages with Sid, I asked him about this. I still have a printed copy of his reply to the effect that he really didn't remember why he'd called these swords espadas anchas - an open and honest reply typical of the man.

F.

F.

There is evidence that short swords were carried by some provincial units in Mexico, such as the Lanceros de Veracruz, but the swords of the soldados de cuera seem always to have been the espada ancha - the full size broadsword.

G.

G.

A soldado de cuera in late-Spanish Era California, José Amador, said in his oral history, recorded in 1877, that his unit's swords were "four to five Flemish spans long" (cuartas flamencas), long enough for the officers to use them as walking sticks.

H.

H.

Since each presidio was required to arm and equip itself, the Model 1728 cavalry broadsword was not the only weapon used by the soldados de cuera, but it seems to have been one of the most common, with fragments discovered at archaeological sites across what once was Spain's Provincias Internas. Other kinds of swords purchased by presidios included the Model 1799 cavalry broadsword, and cup hilted swords. In the uncertain and underfunded supply system of the northern frontier, it was not unusual to find regulation sword blades with non-regulation hilts, and vice versa. But likewise, it was not uncommon to find examples of the light, well-balanced, and sturdily made Model 1728 broadsword still in use by presidial soldiers half a century and more after the manufacture date inscribed on their blades.

I.

J.

J.

Through this new exhibit, and the artistry of John Logan, we now have a proper example of the kind of weapon Spain's frontier soldiers long relied upon, and an opportunity to correct a longstanding error of identification.

Images:

A., D., I, and J. The replica M1728 Spanish cavalry broadsword created for Mission San Juan Capistrano's museum by John Logan. Note the attention detail, including the braided copper wire grip and the engraving on both sides of the blade, copied exactly from original examples. John also "aged" the sword slightly so that it wouldn't look too new.

C. An original M1728 Spanish cavalry broadsword, Arizona Historical Society.

E. A machete used to illustrate the article "Espada Ancha: Swords of Mexico and Spanish Colonial America," Viking Sword website. http://www.vikingsword.com/ethsword/espadaan/index.html

F. A Lancero de Veracruz, 1769. This soldier of a provincial unit carries a short sword, a

machete, on a shoulder belt.

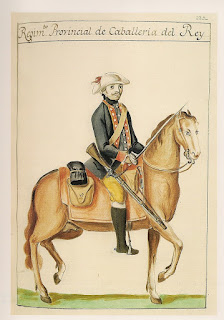

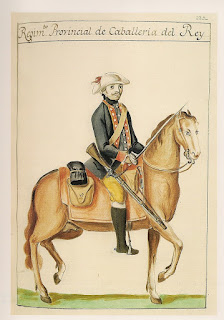

G. A soldier of the Regimiento Provincial de Caballeria del Rey, ca. 1771 carries a full length sword, quite likely the M1728 broadsword..

H. José Cardero's portrait of a presidial soldier of Monterey, California, 1791. Note that he carries a full size sword but with a cup hilt.