Out of the night,

When the full moon is bright,

Comes the horseman known as Zorro.

This bold renegade

Carves a "Z" with his blade,

A "Z" that stands for Zorro.

Zorro, Zorro, the fox so cunning and free,

Zorro, Zorro, who makes the sign of the Z.[1]

As a child, I loved

Zorro. The masked and mysterious hero

with the swirling cape and flashing rapier, dashing black clothes, and magnificent

stallion; his daring attacks, chases and escapes, even his unexplained urge to

monogram with his sword nearly everything, including people he didn’t like. How could any little boy not love Zorro? And, though you might have trouble believing

me after reading this essay, I must admit that for all these same reasons I

still love Zorro. I love him even though he drives me crazy, both historically

and logically.

Let’s start with

history. Zorro is obviously a fantasy

but the stories are set in an actual place and time – California of the early

19th century. I’ve spent much

of my life trying to reconstruct the material world of Spanish and Mexican

California authentically, so the factual errors both large and small that I

find throughout the nearly 100 years of Zorro stories, books, films, television, plays and comics go far beyond just annoying me.

And it isn’t just me. The

historian Abraham Hoffman wrote that the biggest problem he had with the Zorro

legend was, “its existence in a historical vacuum . . .” One that is so unlike

the real early California that the, “story might as well have taken place on

Mars.”[2]

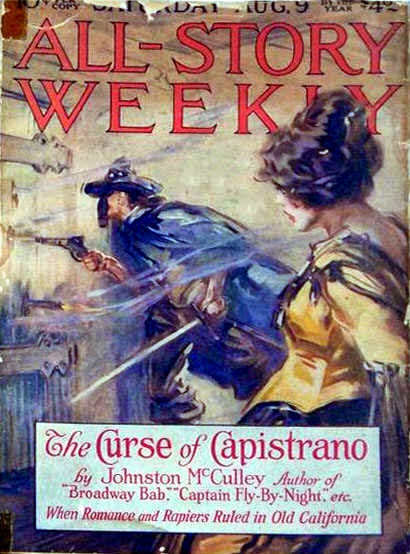

Johnston McCulley (1883 -

1958), who created Zorro for a 1919 pulp adventure story, The Curse of Capistrano, was a former reporter for the

sensationlist Police Gazette. And though an online biography says that

McCulley was a history buff, it’s clear from his experience both as a crime

reporter and pulp fiction author that he wasn’t someone who let facts get in

the way of a good story.[3]

McCulley’s The Curse of Capistrano (later published

in book form under the title, The Mark of

Zorro) is set in an early California that is nothing like the original. It is instead an imagined realm that imposes

a Three Musketeer-like society with its

taverns, wine guzzling, honor codes, duels, skilled fencing and episodic adventures

on top of a travel poster view of Spanish California containing grand

haciendas, sleepy pueblos and orderly missions.

McCulley, the alleged

history buff, didn’t seem to know, or perhaps care, that the real Spanish

California was a remote, isolated and rather poor province. It became far poorer still when Mexico’s wars

of liberation broke out in 1810, ending the vital government supplies

shipments. In the decade that followed,

just the time that most versions of Zorro are set, California endured

grinding poverty – not famine, for locally grown food was abundant – but the lack of nearly every kind of manufactured item. With

foreign trade officially forbidden (and thus clandestine and unreliable) even

the soldiers’ uniforms were often reduced to tatters. Mission trained Indians made most of the shoes, blankets,

riding gear, clothing fabrics, furniture, ironwork and much else needed by the Spanish people of this abandoned province.

There were also very few

people classed as "Spanish" in California during this era. By 1820, those

identified as whites and mixed bloods amounted to only about 3,270 individuals living

between San Francisco Bay and San Diego.

Most moderate-sized towns in California today have more residents than that.[4] Since families were large and

intermarried widely, and most men served in the military at one time or another, it’s likely

that if there were a real Zorro who crossed swords with the soldiers or was pursued by a squad of

cavalry, he could count among his opponents quite a few cousins

and uncles.[5]

Just a few examples of

things McCulley included in his story that never existed in Spanish California

are inns, large fireplaces, pots of locally-produced honey, grand houses with

jewel-encrusted furniture, balconies, a town named Capistrano (it was a mission), a presidio (fort) in Los Angeles, and

eucalyptus trees (introduced to California in the 1850s).

But McCulley’s biggest historical

error pretty much makes his whole story impossible. Whether deliberately or through simple

ignorance, McCulley portrays large estates and wealthy rancheros in Spanish

times (1769-1821) when, in fact, there were very few ranches and these were comparatively small and

unimportant holdings granted to retired or invalided soldiers. Instead, the majority of land and livestock in

those times was in the hands of the Franciscan missions. It was not until the Mexican era (1822-1848) that

the most important soldiers and political leaders made themselves wealthy and

powerful by breaking up the missions and then taking their lands, animals,

property and Indian laborers for themselves.[6]

So if the rancheros made

their fortunes by oppressing the Franciscan padres and Native Californians, why

would Zorro, Don Diego Vega, want to protect them? He was the son and sole heir of one of the richest and most powerful rancheros in the province and himself the owner of a large estate that must have been formed from lands illegally transferred from their Native Californian owners. The branch of fiction to which Zorro belongs

is about heroes who protect those they identify with and who can identify with

them. Robin Hood was a Saxon noble who

protected Saxon peasants from Norman conquerors. The Scarlet Pimpernel, on whose stories

McCulley is said to have based Zorro, liberated French aristocrats because he

was also an aristocrat – English, of course, but fluent in the French language and culture and married to a French gentlewoman. Even Batman, for heaven's sake, fights

criminals because he himself was the victim of a crime. But a member of the oppressing class

protecting those they oppress is not only illogical but also patronizing.

Some of Zorro’s later

interpreters tried to improve the believability of McCulley’s story. His hero’s first film appearance, The Mark of Zorro, with Douglas

Fairbanks (1920), gives a better idea of the date, “nearly a hundred years

ago,” – so, about 1820. We’ve

already seen that this places the events of the story squarely in the period of California’s

greatest poverty and isolation and, of

course, at a time when there were no great ranchos or ranchero class. Tyrone Power’s version of this same title,

released in 1940, makes the date of 1820 definite. It also takes the mention in the Fairbanks

film of Don Diego Vega’s (now de la Vega's) Spanish education – which

McCulley did not include - and makes it a much bigger part of the story. The 1940 Mark of Zorro also changes much of the plot, introduces new characters,

eliminates others and gives us more lavish sets. None of this does much for authenticity, yet

the changes were folded into the hero’s evolving biography when Disney’s

television series, Zorro, premiered

in 1957, not long before Johnston McCulley’s death.[7]

I have little to say about the 1998 movie, The Mask

of Zorro, starring Antonio Banderas.

The plot, production design, and the action

sequences that echo Chinese martial arts films, places

this piece so far into the realm of fantasy that it removes itself altogether

from any discussion of its historical value.

None of these major

versions of Zorro, and certainly not the minor ones, ever overcame the

greatest plot flaw in the story – Don Diego’s role as a leading member of the oppressing

class who nevertheless protects the oppressed.

Only when the Chilean-born novelist Isabel Allende brought out her

novel, Zorro (2005), did something

like a plausible reason emerge. In her telling, Don

Diego is one-quarter Native American and grows up enjoying close ties of family

and affection with the local Indian tribe.

I had some hope for this

novel but, I must admit, I couldn’t finish it. The author has the kind of personal

credentials that should have made this a much better book. She is a widely respected and honored

novelist. She is related to the late President

Salvador Allende of Chile, who in his early career was not unlike Zorro in outlook, championing the causes of the downtrodden and oppressed. He was ruthlessly deposed and probably murdered by his

nation’s military who then carried out a "Dirty War" against any and all suspected dissidents. Spanish is Isabel Allende's first

language and she has lived in California now for about thirty years. All of the original Spanish and English

language documentation of early Californian life and history were open to her

and the surviving historic sites and museum collections were also available. What better assets could one have to break

the mold, defy the clichés and tell a new Zorro story, one that is both believable and even mature?

Instead, Allende chose to

reinforce and explain the most traditional versions of the Zorro story, especially

those from the Disney television series. For example, she includes a backstory for Sergeant Garcia, preferring Disney’s

fat coward reminiscent of Sancho Panza to McCulley's powerfully built bully, Sergeant Gonzalez, of The Curse of Capistrano. Allende incorporates almost all of the past historical errors and invents new ones of her own: haciendas

covered with blossoming bougainvillea plants (introduced to California in the

late-19th century), California Indian girls wearing rabbit skin

boots (they always went barefoot), Indian men with mysterious powers to control wild horses with a whisper, a band of pirates straight out of Hollywood central casting attacking the de la Vega hacienda with knives in their teeth, a standard-issue dread prison

fortress – and we won’t even list the countless historical errors found in her

passages about Don Diego’s life in Spain and adventures in Louisiana, which

form the bulk of the book. It was actually at the point of Zorro’s return

to California and his adventure in liberating his imprisoned father that I

finally abandoned the novel in disgust.[8]

Clearly, Zorro has never belonged in a truly historic setting and perhaps he never will. Really, I shouldn’t be surprised. When has there ever been a believable retelling of Robin Hood – one set in an authentic 12th century

England? And if there were, would anyone except a few scholars of the Middle Ages really care? Isn’t Howard Pyle’s merry

highwayman or Errol Flynn’s green-tighted swaggerer a lot more fun than some

uncouth Saxon poacher and robber living in a flea-infested hut in the cold,

damp depths of a real Sherwood Forest?

Why should I worry about the muddled view of Spanish California that seems

to be necessary for Zorro to emerge triumphant?

I suppose it’s because I

love the reality of early California too much.

I know some might not find it colorful enough - the simple adobes, plain

clothes, and unsophisticated ways. But they

were real, and so was the breathtaking

beauty of the landscape and the strange mixture of cultures that gathered there – Spanish, Mexican,

Native Californian, French, Russian, Native Alaskan, Siberian and American. I really hate the fact that authors and filmmakers have found the

place I love and understand to be so dull and uninteresting that it must be

tarted up to sell to the masses. And so,

though the boy in me still loves Zorro, the man in me wishes that, since Zorro is the only lens through which most of the world sees early California, that it was one that grownups could believe in too.

In my next post about Zorro,

I’ll look at the illogical elements that I believe weaken the story, especially the development of Zorro’s signature costume, weapons and accouterments.

*My thanks to Ross Kimmel for pointing out that it was Sergeant Garcia

in the Disney television show, not Sergeant Gonzales, as I wrote in an earlier

version of this post.

A. Still from the opening titles of Walt Disney's Zorro, c. 1957: http://www.jinni.com/tv/zorro-1957/cast-crew/

B. Guy Williams as Zorro, c. 1957: http://www.briansdriveintheater.com/guywilliams.html

C. Douglas Fairbanks as Zorro and Wallace Beery as Sgt. Garcia in The Mark of Zorro (1920): http://www.historiasdecinema.com/2011/09/douglas-fairbanks/

D. The cover to All-Story Weekly, featuring "The Curse of Capistrano," by Johnston McCulley, 1919: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Curse_of_Capistrano

E. This poster for the 1915 Panama San Diego World's Fair shows the kind of idealized early California that probably influenced Johnston McCulley: http://media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/62/4e/4f/624e4fb368464a683b52e03d7a03ef2b.jpg

F. Los Angeles in 1820 was a tiny, dusty pueblo, and remained

so for decades. This eyewitness drawing

was made by William Rich Hutton in 1847. From the California Historical Society Collection at the University of Southern California: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll65/id/19747

H. After the success of The Mark of Zorro, Douglas Fairbanks (seen here with Mary Astor) starred in a sequel, Don Q Son of Zorro (1925). This movie moved the setting from California to Spain.

I. Mission San Gabriel, located near to the Pueblo de Los Angeles, figures in many versions of the Zorro story. This eyewitness picture painted by Ferdinand Deppe in 1832 shows the mission and its inhabitants looking much as they would have in Spanish times: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Deppe

J. The irony of Don Diego Vega - Zorro - a leading member of California's ruling elite aiding the very people whose exploitation built his family fortune somehow eluded Johnston McCulley. From, "Zorro Frees Some Slaves," West Magazine, 1946. From Zorro, the Legend Through the Years: http://www.zorrolegend.com/origin/mcculleystories.html

K. One of the handsomest actors to don the mask, Tyrone Power starred in The Mark of Zorro in 1940: http://becuo.com/tyrone-power-zorro

L. Antonio Banderas rides in the cartoonish The Mask of Zorro (1998)

M. The cover to the first English translation of Isabel Allende's Zorro (2005).

M. The cover to the first English translation of Isabel Allende's Zorro (2005).

N. Detail from the watercolor, "View Taken Near Monterey," by Richard Brydges Beechy, 1827, Honeyman Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

P. Errol Flynn in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938).

Q. California's golden poppies growing along the coast: http://www.publicdomainpictures.net/view-image.php?image=6109&picture=california-poppies

R. Douglas Fairbanks in The Mark of Zorro (1920): http://www.dvdtalk.com/reviews/9283/douglas-fairbanks-collection-the/

Notes

[2]

Abraham Hoffman, “Zorro: Generic Swashbuckler,” The Californians, Sept.-Oct., 1985.

See also, http://www.authorsden.com/visit/author.asp?id=89901,

for Dr. Hoffman’s vitae.

[3]

http://www.vintagelibrary.com/pulpfiction/authors/Johnston-McCulley.php

[4]

City Data.com: http://www.city-data.com/city/California3.html

[5]

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of

California, Vol. II. 1801-1824 (San Francisco, The History Company, 1886),

392-393. Population of Los Angeles, 349.

[6]

The story of the “secularization” of California’s missions during the Mexican

era, leading to the transfer of land, property, livestock and laborers to the

Californio elite is told in too many places, starting with every Fourth Grade

history textbook in the state, to need a reference here. But if one does, Hubert Howe Bancroft’s

foundational histories of California are available online, including volume 3,

1825-1840: http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=yale.39002070864518;view=1up;seq=13

[7]

Matthew Fox on his webpage, “The Legacy of the Fox: A Chronology of Zorro,”

undertakes the unenviable task of trying to arrange the events of what seems to be

every known English-language story, book, film, television series and even comic

book into a comprehensible time line. http://www.pjfarmer.com/woldnewton/Zorro.htm

[8]

The only “pirate” raid on California was the attack by the Argentine privateer,

Hypolite Bouchard, on coastal settlements in 1818, more than twelve years after

the event described in Allende’s novel.

_cover.jpg)