The "torreón" or

defensive tower at Manzano, New Mexico - Library of Congress

The "torreón" or defensive tower at Manzano, New Mexico was part of a fortified village, very similar in form and function to the Spanish Borderland's presidios. The difference was that this was a civilian settlement. Manzano's torreon is believed to have been built in about 1840.

Manzano was just one of several fortified villages in this region, and is located in central New Mexico, in a range of mountains southeast of Albuquerque. According to an article by Dixie Boyle, cited below:

"Upon their arrival in Manzano, the first settlers built a torreón and grouped their houses close together with portholes for shooting. While additional settlers built homes and planted crops, several lookouts were posted to constantly scan the landscape for any raiders heading their way.

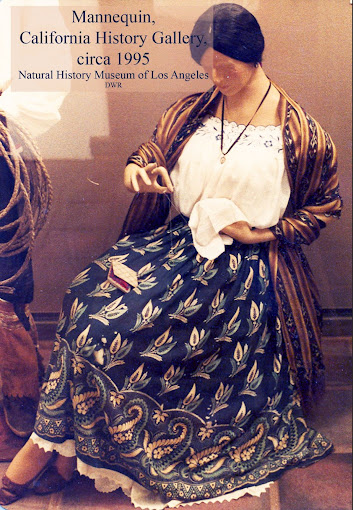

Wayside from El Rancho de las Golondrinas, New Mexico

When a raiding party was spotted, the lookout immediately began beating a drum as hard as possible, alerting the entire village to an incoming attack. Another lookout rushed to the church and rang the church bells until everyone was safe inside the torreón."

Elevations of the torreón at Manzano

These defenses, of course, were meant to protect against indigenous tribes. Nevertheless, according to Boyle: "Throughout the years, the people of Manzano developed a friendship with the Apache. They traveled to the state’s eastern plains, where they hunted buffalo together. They accepted many of the customs of the Apache, and because of this association they were able to survive in the unruly country."

For more about the history of Manzano and its architecture, see: "An Early fort on the New Mexico border" by Dixie Boyle https://issuu.com/enchantmentma.../docs/2305_soco/s/23805283

The Torreon, Manzano, Torrance County, NM, Library of Congress (includes plans). https://www.loc.gov/item/nm0066/